Medical scribes assist health care providers with medical

documentation, thus freeing providers’ time for clinical work.

In 2015, Grand Valley State University (GVSU) partnered with

Helix Scribe Solutions (HSS) to educate medical scribes with

classroom and clinical training, including interprofessional

education (IPE) created by the Midwest Interprofessional

Education and Research Center. This study explored the

impact of an academic scribe training program, including the

effect of IPE on scribe student perceptions of teamwork and

to determine the factor(s) associated with scribe documen-

tation recording accuracy. From August 2016 to October

2018, 196 students consented to participate. Students were

asked to complete the Interprofessional Education Percep-

tion Scale (IEPS) and Entry Level Interprofessional Question-

naire (ELIQ) tools before and after their educational program.

Differences between overall pre- and post-questionnaires

were significant (p<0.05). IEPS subscales, Perception of

Need for Cooperation, Perception of Actual Cooperation,

and Understanding Others’ Values were significant (p<0.05).

The ELIQ subscale Interprofessional Interaction showed sig-

nificant positive scoring (p<0.05). Program evaluations

showed the curriculum prepared the students to work in

emergency department interprofessional teams. Logistic

regression modeling indicated that students’ grade point

average was significant in predicting whether a scribe would

have fewer deficiencies per chart on average as scribe

employees. J Allied Health 2021; 50(4):263–268.

MEDICAL SCRIBES are a major, emerging, new work-

force group in the United States. Medical scribes assist

providers with patient care documentation at the bed-

side, in real-time, and are usually unlicensed allied

health professionals. Emergency Department staff have

used scribes to assist with patient documentation as

early as 1974.

1

The increased digitalization and stan-

dardization of medical records that resulted from the

Affordable Care Act (ACA)

2

has stimulated the growth

of this workforce.

3

With the increased complexity of

electronic health record (EHR) charting, documenta-

tion can occupy as much as 44% of a provider’s time.

4

Clinical environments under pressure for productivity

and efficiency are well suited for the integration of med-

ical scribes.

To meet an increased need and to provide role clarifi-

cation, the Joint Commission defined a scribe as “a

trained medical information professional who special-

izes in charting physician-patient encounters.”

5

Accord-

ing to the Joint Commission, scribes should be trained

on the safe use of EHRs before working in the highly

regulated healthcare environment. A recent federally

funded study reported that properly trained medical

scribes can safely use EHRs and improve documenta-

tion quality.

6

Medical scribes should also be prepared to

work in environments that require interprofessional

teamwork, mutual respect, and open communication.

7

However, the literature is limited on how scribe educa-

tion impacts work performance.

8–11

Scribe education focuses on medical documentation

competency to identify and document key elements of

the history of present illness (HPI), physical exam (PE),

and review of systems (ROS). Most scribes are required

to document a majority of the patient visit which

requires proficient knowledge and practical use of med-

ical terminology, medication information, the patho-

physiology of body systems, coding and billing, labora-

tory definitions and values, and medical equipment,

among others.

With increased emphasis on patient care quality and

safety, providers and policymakers recognize that health-

care workforce shortages necessitate increased collabo-

ration and teamwork across health professions.

12

Uti-

263

INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

The Impact of Interprofessional Education and Practice

on Medical Scribe Success Working in the Emergency

Department

Jean Nagelkerk, PhD

1

Ryan Cook, MBA

2

Jeff Trytko, MS

1

Lawrence Baer, PhD

3

Joseph Lorenz, MS

1

Emily Callis, MS

4

From

1

Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, MI;

2

Helix Scribe

Solutions, Grand Rapids, MI;

3

Independent Contractor, Belmont, MI;

and

4

Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI.

The authors report no funding or conflicts of interest related to this

study.

IP2381—Received Mar 26, 2021; accepted June 14, 2021.

Address correspondence to: Mr. Jeff Trytko, College of Health Profes-

sions, Cook-DeVos Center for Health Sciences, Grand Valley State

University, 301 Michigan St. NE, Suite 400, Grand Rapids, MI 49503-

3314, USA. Tel 616-331-2729, fax 616-331-5640. trytkoj@gvsu.edu.

© 2021 Assoc. of Schools Advancing Health Professions, Wash., DC.

lizing interprofessional collaborative practice is essen-

tial to optimally educating the next generation of

healthcare practitioners and improve collaborative

practice.

13

For scribes to work effectively on interpro-

fessional teams, they must learn effective communica-

tion techniques.

Helix Scribe Solutions, a for-profit scribe staffing

company, partnered with Grand Valley State Univer-

sity (GVSU) to create the GVSU Scribe Academy.

Graduates from the Academy become part-time med-

ical scribes through Helix working in emergency depart-

ments. When developing the program, the authors dis-

covered for-profit companies had designed scribe

workforce training and employment programs, but lim-

ited sharing of curricular details.

8–10

GVSU faculty and

staff created the curriculum for the GVSU Scribe Acad-

emy that includes 40 hours of theory and 40 hours of

clinical training. Scribe didactic knowledge is assessed

by passing an examination of the theory portion with a

minimum of 85% to be eligible for clinical training. Cur-

riculum information is located in Appendix 1. As part-

ners of the Midwest Interprofessional Practice, Educa-

tion, and Research Center (MIPERC), elements from

the core IPE content was incorporated into the Acad-

emy curriculum. MIPERC was established in 2007 as an

inter-institutional infrastructure to transform health-

care education and practice.

12–14

Interprofessionl educa-

tion (IPE) was added to the curriculum to smooth the

process for scribe students integrating into the emer-

gency department team. The content includes IPE core

competencies, the scope of practice and professional

role blurring, patient safety, effective communication

behaviors, and team conflict and resolution. The Acad-

emy training is free for all eligible students, with the

agreement to commit to this program and employment

for at least 18 months.

A study was developed to determine the usefulness

of a robust curriculum including IPE content in the

scribe training and to determine factors affecting scribe

student success in the program. The key questions for

the study include: 1) does the inclusion of IPE content

in the medical scribe training curriculum improve per-

ceptions of interprofessional teamwork through clinical

training? and 2) what characteristics from the students’

application materials predict they will be successful

medical scribes?

Methods

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design with the

scribe program as the independent study variable.

Dependent variables were collected from the scribe pro-

gram application and screening materials which

included typing speed, medical terminology test results,

university program major, class level, career and aca-

demic goals, and grade point average (GPA). All pre-

screening was conducted by the GVSU Scribe Director

and support staff. Scribe Academy graduates became

part-time Helix Scribe Solutions employees.

This research was approved by the GVSU Institu-

tional Review Board (IRB study #16-113-H-GVSU).

Students completed an informed consent and demo-

graphic form in addition to application materials prior

to starting the Academy.

Tools and Measures

Students completed the Interdisciplinary Education

Perception Scale (IEPS) and the Entry-level Interprofes-

sional Questionnaire (ELIQ) tools before starting the

Academy and after their clinical rotations. Both assess-

ments were completed online in the learning manage-

ment system Blackboard®, and results were downloaded

to a spreadsheet. The IEPS was tested for validity and

reliability for assessing perceptions of interprofessional

care.

15

This was a tool with 18 items and four subscales:

competency and autonomy (CA), perceived need for

cooperation (PNfC), perception of actual cooperation

(PAC), and understanding others’ values (UOV). The

PNfC subscale addresses perceptions about the collabo-

rative environment.

The ELIQ was used to measure dimensions of team

communications and teamwork and has been tested for

reliability and validity.

16

This tool contains three sub-

scales: communication and teamwork style (CTS),

interprofessional learning (ILS), and interprofessional

interaction (IPIS). Total questions of 27 are divided

evenly into each category utilizing a 5-point Likert-type

scale. This tool categorized scores for each section into

three groups: positive, neutral, and negative. Communi-

cation and style comfort items were included in the

CTS subscale. Respondent’s experience learning with

other health professions was measured in the ILS sub-

scale, and the IPIS included items related to collabora-

tive practice perceptions and communication among

health professions.

Scribes completed a program evaluation at the end

of clinical training that included narrative questions

about the course and working on the interprofessional

emergency department team; as an example one ques-

tion asked, “What efficiencies are gained in the emer-

gency department by having a scribe work with a

provider?” Students were asked to complete this by the

program director upon the decision of their pass/fail of

the clinical training.

Scribe success was measured through standardized

charts drafted by Helix scribe employees. Standard

monthly chart audits were conducted. A selection of 12

charts per month per scribe were audited by a team of

experienced full-time Helix scribes. Charts were evalu-

ated on three criteria including accuracy, narrative flow,

and spelling and grammar. The numbers of deficiencies

per chart were tracked and averaged on a central

spreadsheet maintained by Helix leadership.

264

NAGELKERK ET AL., IPE and Medical Scribe Success in the ED

Data Analysis

Demographic data were summarized with descriptive

statistics. The sample size, normality, and symmetry of

differences were assessed to determine appropriate sta-

tistical analysis.

The direct effect on scribe student interprofessional

attitudes was tested by comparison of results from

instruments completed at baseline to those completed

at the end of clinical training. Two assessments were uti-

lized for this: IEPS and ELIQ. Changes in relevant

knowledge and perception were tested with paired t-

tests. This included the examination of four factors

measured with IEPS. The ELIQ instrument grouped its

underlying ordinal scale into three ordinal categories

and so Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank was used.

Qualitative data from program evaluation surveys

were used to examine emerging themes. The author

team reviewed the results and coded responses based on

common themes that emerged. The consensus was

established by three of the authors. Binary logistic

regression was used to look at what factors were signifi-

cant in predicting scribe success. The outcome variable

of interest for this model was defined as whether the

student had 4 consecutive months with an average of

three or fewer deficiencies per chart audit. This process

is proprietary to Helix Scribe Solutions per lack of

available resources in the literature. All factors were put

into the model utilizing a backward method, where the

variable with the highest p-value was removed, until

only significant variables remained. Data analysis was

performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 software.

Significance for all tests was set at p<0.05.

Results

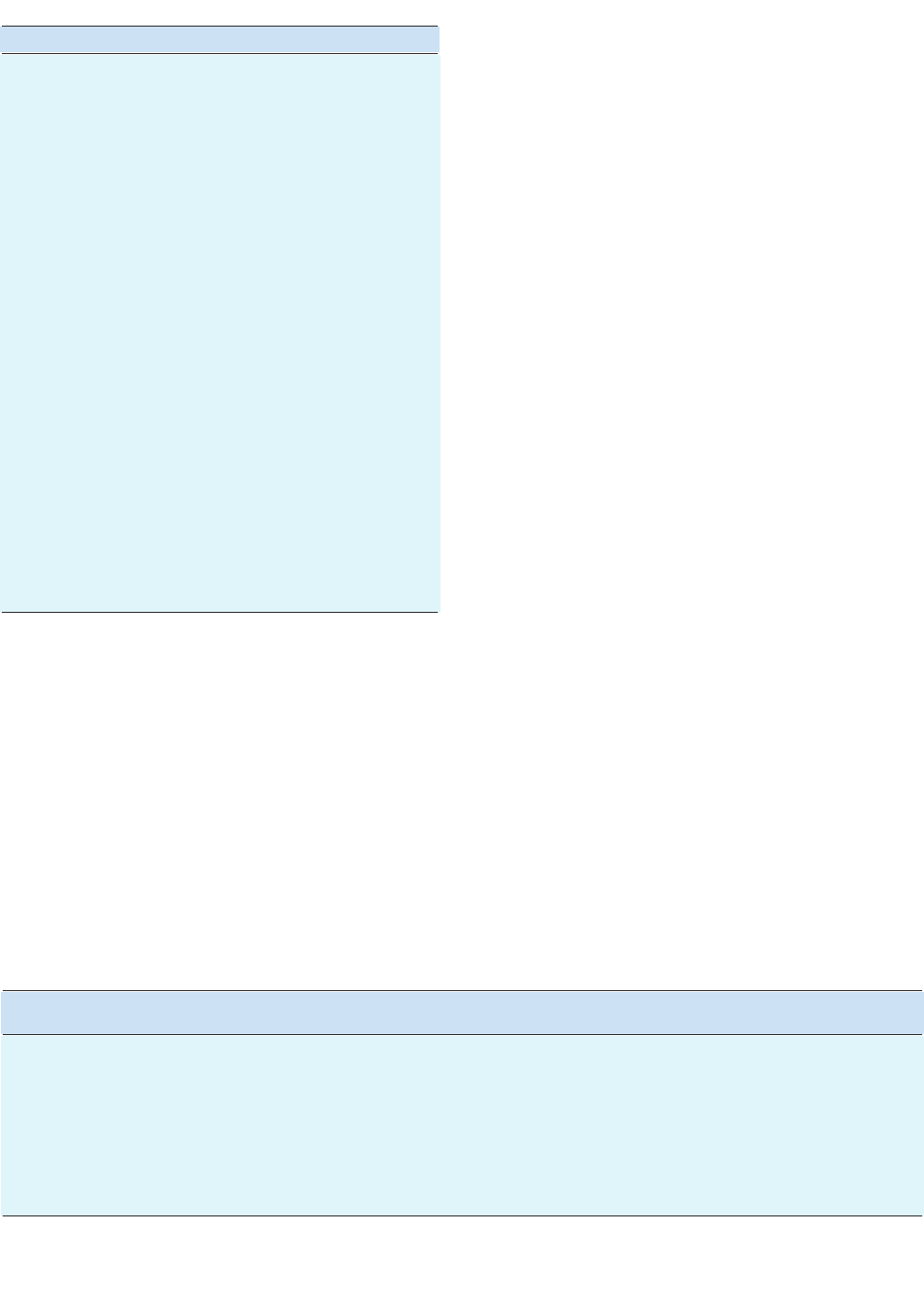

Description of study participants (n=194, Table 1) shows

that 66.3% of participants were female, and most had

not had IPE in the past.

The overall IEPS scores were positive when compared

to baseline values and demonstrated significant (p<0.05)

improvement. Table 2 shows the four measures also

tested within IEPS. All but the competency and auton-

omy subscales were considered significant. The overall

ELIQ and subscale average scores were in the positive

range and were determined to show improved perception

of interprofessional knowledge (p=0.012, Table 2).

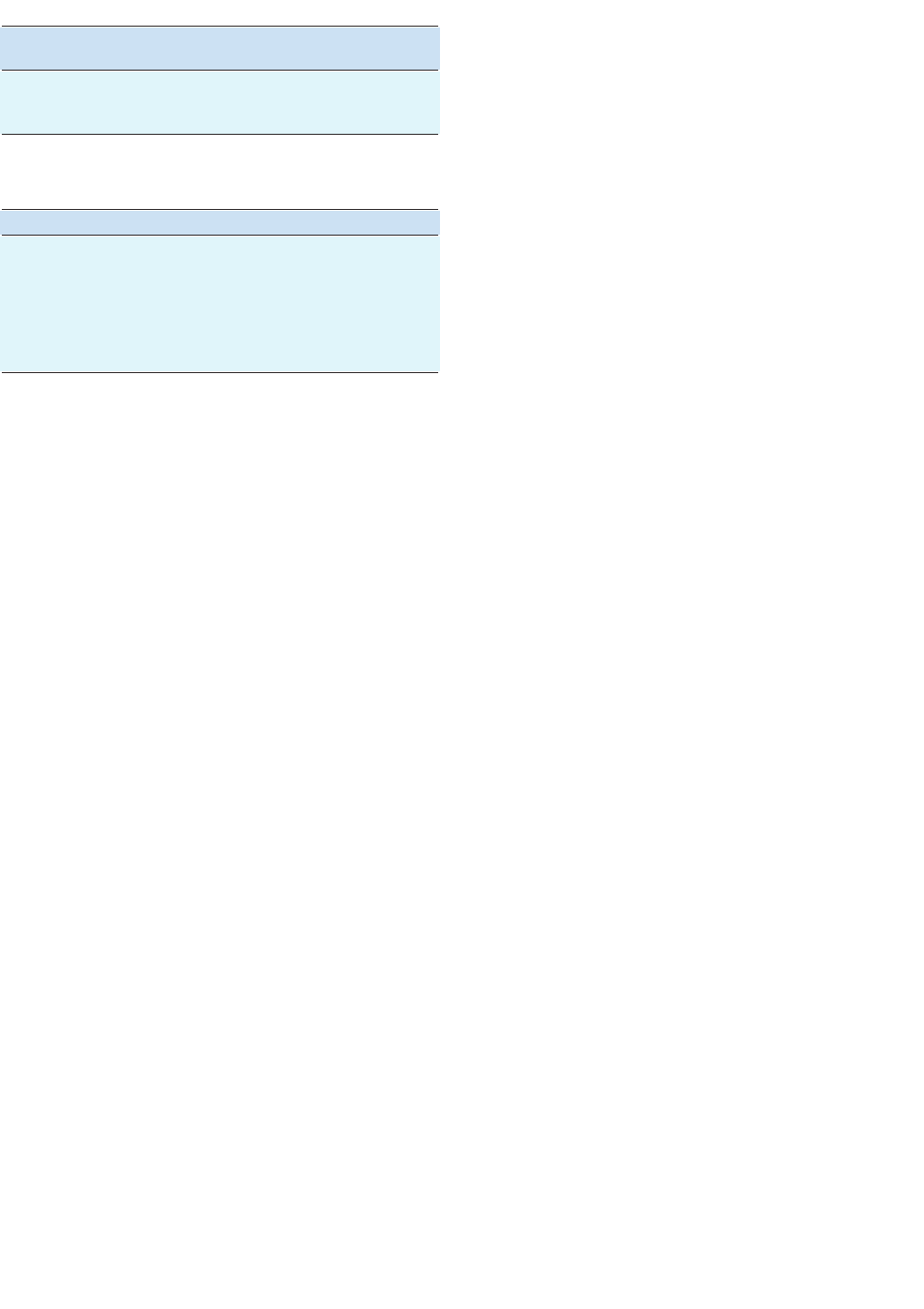

The scribe students completed the program evalua-

tions after 40 hours of clinical training working with

emergency department providers as a team. From the

102 respondents, three themes emerged: 1) focus on

patient care; 2) increased throughput; and 3) decreased

workload (Table 3).

The factors entered into the logistic regression

model and results are listed in Table 4: medical termi-

nology pretest score, whether or not they had prior

Journal of Allied Health, Winter 2021, Vol 50, No 4

265

TABLE 1. Study Participants (n=174)

Characteristics No. (%)

Gender

Male 56 (31.5)

Female 118 (66.3)

Missing 4 (2.2)

Race

Asian 21 (11.8)

Black or African American 6 (3.4)

Caucasian 137 (77)

Multiracial 7 (3.9)

Other 1 (0.6)

Missing 6 (3.4)

Ethnicity

Hispanic 6 (3.4)

Non-Hispanic 167 (93.8)

Missing 5 (2.8)

Education highest degree obtained

High school (enrolled in 4-yr college) 105 (59)

Associate degree/certicate/diploma 27 (15.2)

Baccalaureate degree 33 (18.5)

Master’s degree 2 (1.1)

Missing 11 (6.2)

Prior interprofessional course

Ye s 11 (6.2)

No 162 (91 )

Missing 5 (2.8)

Prior interprofessional education

Ye s 5 (2.8)

No 168 (94.4)

Missing 5 (2.8)

TABLE 2. IEPS and ELIQ Testing Results

Pre vs Post Test

Average Difference SD p-Value

Interprofessional Education Scale (IEPS) (n=119) 3.24 11.15 0.002*

Competency and autonomy 0.96 6.09 0.089

Perception of need for cooperation 0.35 1.63 0.020*

Perception of actual cooperation 1.32 3.71 <0.001*

Understanding others value 0.61 2.34 0.006*

Entry-Level Interprofessional Questionnaire (ELIQ) (n=92) 2.37 8.88 0.012*

Communication and teamwork –1.11 2.73 <0.001*

Interprofessional learning –1.02 4.11 0.019*

Interprofessional interaction 2.39 6.26 <0.001*

* ≤ 0.05.

clinical experience, university program major, level of

credit earned, last degree earned, typing speed, and

GPA. Six of the seven factors were considered insignifi-

cant with a cutoff value of p>0.05. GPA was considered

a significant factor in predicting whether a GVSU

Scribe Academy graduate will have three or fewer defi-

ciencies per chart on average over 4 consecutive

months as an employed scribe.

Discussion

Scribe students’ perceptions of interprofessional educa-

tion and practice improved from baseline to the com-

pletion of the Academy. Most students had no prior

IPE and reported positive perceptions of collaborative

care in their program evaluations, which is similar to

research results in the literature.

17,18

All of the subscales

showed statistical improvement except for an improve-

ment in perceived autonomy. This may be attributed to

the scribes’ scope of practice as allied health profession-

als who are not directly responsible for patient care

decisions (the Joint Commission).

We examined the characteristics of effective scribe

students working on the emergency department team

based on the quality of scribe health records. Of the fac-

tors we evaluated for successful students during the

screening process, GPA showed to be the only signifi-

cant. Higher GPAs may indicate a student’s work ethic

and desire to perform well. Other authors describing

their scribe models did not find having a college back-

ground necessary, yet also stated that scribes experience

a steep learning curve for completing more complex

medical documentation.

9

We found students already

enrolled in a higher education program with at least

two semesters as full-time students are better prepared

with the study habits to be successful in a higher-educa-

tion-based scribe training program.

The literature shows scribe programs best prepare stu-

dents to adapt to providers by including clinical training

in the curriculum. An important aspect of the Academy

was the 40 hours of clinical training that prepared the

scribes to put the Academy theory training and IPE into

practice by “follow in the footsteps” of providers without

stepping on their toes.

10

Yan et al.

10

observed that

provider and scribe teamwork is achieved through a trial

process during shifts. The scribes in Yan et al.’s paper

started scribing after having achieved certification in

another health profession, contrasting with our students

who did not have extensive prior clinical experiences.

10

Our data show the GVSU Scribe Academy curriculum

including IPE laid the foundation for a smooth transi-

tion for building the provider and scribe team.

The GVSU Scribe Academy program evaluations

provided rich data with three themes emerging from

scribe student responses (Table 3). The first theme

related to the student’s satisfaction with their contribu-

tion to assisting providers to focus more on patient

care. They reported how their role through documenta-

tion helped the providers to have uninterrupted face-to-

face time with patients and time for medical decision-

making and coordination of treatment plans. This

study did not evaluate how the scribes helped the

providers specifically, but other studies observed that

scribes assist providers by adapting to their workflow.

11

The physician takes the lead, and the scribe conforms

to their work habits to better fit the provider’s.

Providers also learn how to adapt their work for the

scribe to be a more effective teammate, e.g., verbalizing

physical exam findings in the room.

9,11

The second theme that emerged was the scribe’s

observation of provider patient care throughput

enhanced by the delegation of patient documentation.

This paper’s authors received feedback from providers

on how GVSU Scribe Academy graduates help them

with efficiency and writing high-quality, detailed, med-

ical notes.

19

A PubMed search for “medical scribes” in

April 2020 showed over 35 peer-reviewed papers report-

ing improved provider productivity through patients

seen per shift, decreased time spent for providers docu-

menting, and increases in relative value units. Increased

productivity with a medical scribe assists with more

accurate notes for improved reimbursements leading to

increased revenue.

20–23

The scribe’s contributions to

provider improved throughput can offset the added cost

for scribe training programs and staffing.

24,25

Finally, scribes reported observing a decrease in cleri-

cal workload on providers, allowing them time to focus

more on patient management. One provider told the

authors that having a scribe allows them to focus more

on the clinical needs for the patient, so they can focus

more on the patient’s problem, history, physical exam,

and treatment plan.

18

This is consistent with other stud-

266

NAGELKERK ET AL., IPE and Medical Scribe Success in the ED

TABLE 3. Student Program Evaluation Results

What efciencies are gained in the ED

by having a scribe work with a provider? (n=102) No. (%)

Providers can focus more on patient care 45 (44.1)

Increased patient throughput 38 (37.3)

Decreased workload for providers 19 (18.6)

ED, emergency department.

TABLE 4. Output of Logistic Regression Analysis

Predictor Variable Wald Chi-Squared p-Value

Pretest 0.2221 0.638

Clinical experience 0.8485 0.357

Major 1.2414 0.265

Level of credits earned 2.6475 0.104

Last earned degree 1.9521 0.162

Typing speed 1.8948 0.169

Grade point average* 11.6090 <0.001†

* Estimate = 2.0002. † = 0.05

ies that have reported scribes decreased the time

providers spent documenting in electronic medical

records by 50%.

7,26

Not only do scribes assist with efficien-

cies in patient care flow, but they also aided providers

during clinical shifts to have more time teaching resi-

dents, increasing the quality of their education.

27,28

With

a greater focus on patient-related tasks, this has been

shown to increase provider satisfaction.

29–32

Decreasing

the documentation workload on providers is one solu-

tion to provider burnout.

33,34

Limitations

This study investigated various aspects of a single scribe

program. Our findings may not reflect the “advanced

‘dual-trained’ scribes” who not only focus on medical

documentation but also close care gaps other health

professions can delegate, such as rooming patients and

motivational interviewing.

33,35

At the inception of the

GVSU Scribe Academy, the eligibility criteria were

established to ensure student success. These results do

not reflect the medical scribe workforce not sharing

these same criteria. Additionally, qualitative data could

not be collected from providers to further explore the

benefits of scribing and the role of the scribe as an inter-

professional care team member. Lastly, the lack of an

accrediting body to standardize criteria for professional

certification makes it difficult to compare scribe pro-

gram curriculum and quality.

Conclusion

The GVSU Scribe Academy was created to assist emer-

gency medicine providers in meeting the growing

demands of medical record documentation. Scribes are

not licensed health professionals and are unable to per-

form patient care tasks, though they contribute to pro-

vider efficiencies by improving medical documentation

and throughput and by enabling increased workload.

Including IPE in the academic core scribe curriculum

had aided students naïve to the healthcare environ-

ment through clinical training and into employment.

Scribe perceptions of providers and teamwork

improved on both the IEPS and ELIQ subscales. The

most successful scribes were those with high GPAs. Fur-

ther exploration is needed on the provider’s percep-

tions of scribe interprofessional competencies and

teamwork characteristics. National standardization of

scribe education would be helpful to ensure the quality

of the scribe workforce.

References

1. Lynch TS. An emergency department scribe system. J Am Coll

Emerg Physicians. 1974 Sep;3(5):302–3.

2. Patient Protection Affordable Care Act. 42 U.S.C, 18001 2010.

3. Bossen C, Chen Y, Pine KH. The emergence of new data work

occupations in healthcare: the case of medical scribes. Int J Med

Inform. 2019 Mar;123:76–83.

4. Hess J, Wallenstein J, Ackerman J, et al. Scribe impacts on

provider experience, operations, and teaching in an academic

emergency medicine practice. West J Emerg Med. 2015 Sep

15;16(5):602–10.

5. The Joint Commission. Standard FAQs: Documentation Assis-

tance Provided By Scribes. Updated 2020 Apr 16. Available

from: https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/standard-

faqs/ambulatory/record-of-care-treatment-and-services-

rc/000002210/ [cited 2020 Aug 12].

6. Ash JS, Corby S, Mohan V, et al. Safe use of the EHR by medical

scribes: a qualitative study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Oct 29.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa199

7. Imdieke BH, Martel ML. Integration of medical scribes in the

primary care setting: improving satisfaction. J Ambul Care

Manage. 2017;40(1):17–25.

8. Baugh R, Jones JE, Trott K, et al. Medical scribes. J Med Pract

Manage. 2012 Dec;28(3):195–7.

9. Gellert GA, Ramirez R, Webster SL. The rise of the medical

scribe industry: implications for the advancement of electronic

health records. JAMA. 2015 Apr 7;313(13):1315.

10. Yan C, Rose S, Rothberg MB, et al. Physician, scribe, and patient

perspectives on clinical scribes in primary care. J Gen Intern Med.

2016 Sep;31(9):990–5.

11. Addesso LC, Nimmer M, Visotcky A, et al. Impact of medical

scribes on provider efficiency in the pediatric emergency depart-

ment. Acad Emerg Med. 2018 Oct 23. https://onlinelibrary.

wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/acem.13544

12. Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core

Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016

update [Internet]. Washington, DC: IPEC; 2016. Available from:

https://hsc.unm.edu/ipe/resources/ipec-2016-core-competen-

cies.pdf

13. Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional educa-

tion: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes

(update). Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2013. http://doi.wiley.

com/10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3

14. Nagelkerk J, Coggan P, Pawl B, Thompson ME. The Midwest

Interprofessional Practice, Education, and Research Center: a

regional approach to innovations in interprofessional education

and practice. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2017 Jun;7:47–52.

15. Luecht R, Madsen M, Taugher M, Petterson B. Assessing profes-

sional perceptions: design and validation of an interdisciplinary

education perception scale. J Allied Health. 1990 Spring;19(2):

181–91.

16. Pollard KC, Miers ME, Gilchrist M. Collaborative learning for

collaborative working? Initial findings from a longitudinal study

of health and social care students. Health Soc Care Community.

2004 Jul 1;12(4):346–58.

17. Kururi N, Makino T, Kazama H, et al. Repeated cross-sectional

study of the longitudinal changes in attitudes toward interpro-

fessional health care teams amongst undergraduate students. J

Interprof Care. 2014 Jul;28(4):285–91.

18. Nagelkerk J, Thompson ME, Bouthillier M, et al. Improving out-

comes in adults with diabetes through an interprofessional col-

laborative practice program. J Interprof Care. 2017 Nov 7;1–10.

19. Helix Scribe Solutions. [cited 2020 Aug 12]. Available from:

https://www.helixscribes.com/Core/Gallery/Spotlights/1000/

20. Dawkins B, Bhagudas KN, Hurwitz J, et al. An analysis of physi-

cian productivity and self-sustaining revenue generation in a

free-standing emergency department medical scribe model. Adv

Emerg Med. 2015;2015:1–9.

21. Bank AJ, Gage RM. Annual impact of scribes on physician pro-

ductivity and revenue in a cardiology clinic. Clinicoecon Out-

comes Res. 2015;7:489–95.

22. Earls ST, Savageau JA, Begley S, et al. Can scribes boost FPs’ effi-

Journal of Allied Health, Winter 2021, Vol 50, No 4

267

ciency and job satisfaction? J Fam Pract. 2017 Apr;66(4):206–14.

23. Zallman L, Finnegan K, Roll D, et al. Impact of medical scribes

in primary care on productivity, face-to-face time, and patient

comfort. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018 Jul;31(4):612–9.

24. Hegstrom L, Leslie J, Hutchinson E, et al. 560: medical scribes:

are scribe programs cost effective in an outpatient MFM setting?

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jan;208(1):S240.

25. Walker K, Ben-Meir M, Dunlop W, et al. Impact of scribes on

emergency medicine doctors’ productivity and patient through-

put: multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019 Jan 30;l121.

26. Taylor KA, McQuilkin D, Hughes RG. Medical scribe impact on

patient and provider experience. Milit Med. 2019 Feb 27. Avail-

able from: https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-arti-

cle/doi/10.1093/milmed/usz030/5366283

27. Delage BS, Sherman K, Halaas G, Johnson EL. Getting the

predoc back into documentation: students as scribes during

their clerkship. Fam Med. 2020 Apr 3;52(4):291–4.

28. Wegg B, Deibel M, Kiernan C. 162 advancing resident training

with the use of scribes. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Oct;64(4):S59.

29. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, Kogan BA. Scribes in an ambula-

tory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol.

2010 Jul;184(1):258–62.

30. Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, et al. An ED scribe program is

able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J

Emerg Med. 2014 May;32(5):399–402.

31. Gidwani R, Nguyen C, Kofoed A, et al. Impact of scribes on

physician satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and charting effi-

ciency: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2017

Sep;15(5):427–33.

32. Sattler A, Rydel T, Nguyen C, Lin S. One year of family physi-

cians’ observations on working with medical scribes. J Am Board

Fam Med. 2018 Jan;31(1):49–56.

33. Reick-Mitrisin V, MacDonald M, Lin S, Hong S. Scribe impacts

on US health care: benefits may go beyond cost efficiency. J

Allerg Clin Immunol. 2020 Feb;145(2):479–80.

34. Yates SW. Physician Stress and Burnout. Am J Med. 2020 Feb;

133(2):160–4.

35. Martel ML, Imdieke BH, Holm KM, et al. Developing a medical

scribe program at an academic hospital: the Hennepin County

Medical Center experience. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018

May;44(5):238–49.

Published online 1 Dec 2021

www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asahp/jah

© 2021 ASAHP, Washington, DC.

268

NAGELKERK ET AL., IPE and Medical Scribe Success in the ED

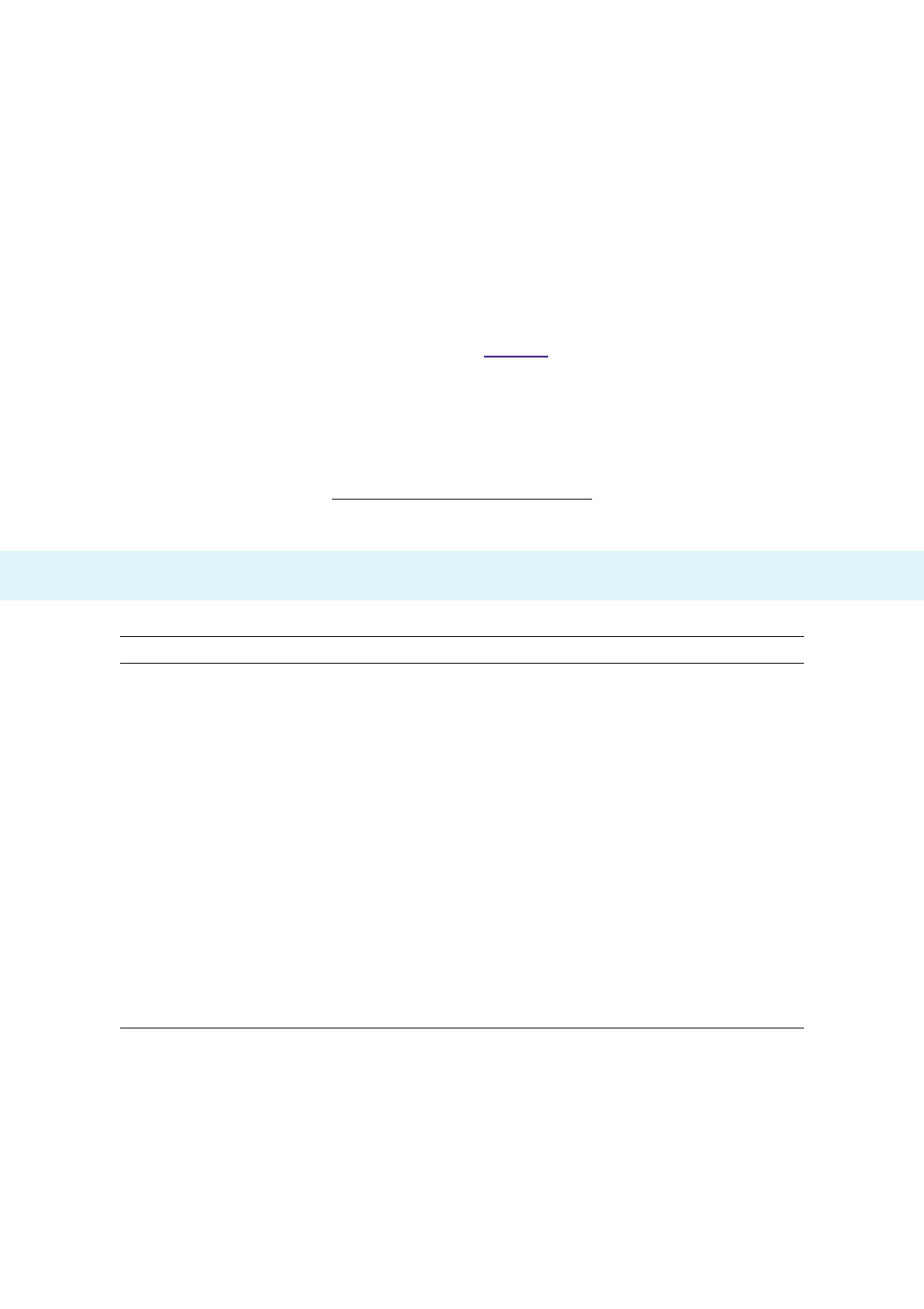

Content Format Hours

Scribe academy kickoff - orientation Online 2

GVSU HIPAA & BBP training modules Online 2

Common ED medications Online 2

Joint Commission Online 1

What is a medical scribe? (professional role identity) Online 0.5

Introduction to the history of present illness note Online 0.5

Common ED procedures and equipment Online 2

ED radiology imaging Online 1

Laboratory tests Online 1

Physical exam and review of systems Online 3

Basics of the medical note Online 4

Basics of medical coding and billing Online 4

Body systems/pathophysiology Online 8

Interprofessional education Online 1

Introduction to electronic medical record and charting simulation In-person 3

Charting simulation, introduction to clinical training and ED In-person 4

Comprehensive nal exam Online 1

Clinical training (5 shifts) Clinical 40

Total 80

ED, emergency department.

APPENDIX 1. GVSU Scribe Academy Curriculum